DarkRange55

We are now gods but for the wisdom

- Oct 15, 2023

- 1,996

The fundamentals in mining are ever-changing, which is exactly why the Lassonde curve is sinusoidal and why so many junior miners go bust. Mining companies are still being hammered by inflation. Even giants like Newmont, the world's largest gold miner, and Barrick are struggling to control labor costs. The basic math is that the all-in sustaining costs (AISC) of running a mine are rising faster than the gold price. An ounce of gold in the ground is worth less today than it was a few years ago. While this dynamic could eventually reverse, persistent inflation means the problem may last for another half-decade.

Junior gold miners in particular are like playing Russian roulette. The business is extremely capital intensive, often located in high-risk or high-labor-cost jurisdictions, and most of the world's easy, low-cost deposits have already been mined. Costs are relentlessly rising—labor is getting more expensive worldwide, mining expertise is scarce, and critical processing chemicals cost more each year. On top of that, junior management teams have a reputation for being no more trustworthy than used car salesmen or politicians, with a history of diluting shareholders or engaging in self-serving deals. Storage, transport, and sales logistics also add cost and complexity.

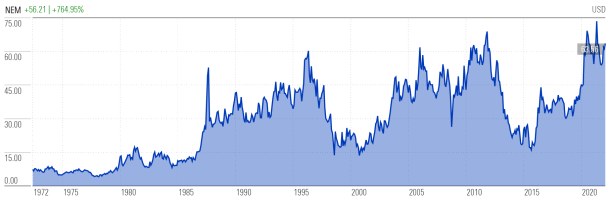

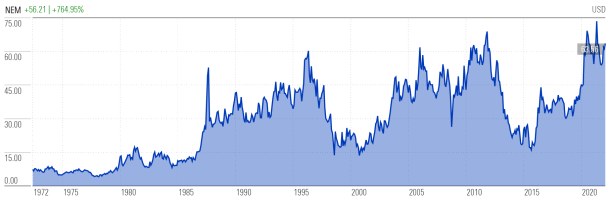

The economics quickly turn ugly if gold prices fall. For example, Harmony Gold (HMY) currently runs with a gross profit margin around 22%. If gold dropped by 40%, profitability would vanish. Mining stocks are capital-intensive, carry huge pricing risk, are inherently low growth, and offer no real moat—they are price takers selling an undifferentiated commodity. Supply is finite and comes in unpredictable, good-or-bad batches. The sector is cyclical, not secular, so it doesn't steadily appreciate over time. By contrast, investors who prioritize cash flow tend to prefer steady, reliable businesses like insurance or beverages.

On top of that, mining stocks carry company-specific risks: poor management, excessive debt, or legal liabilities. They are often more volatile than the price of gold itself, swinging with earnings reports and investor sentiment. Many operate in politically unstable regions, so risks of coups, nationalization, or sudden tax changes are ever-present. Operational problems like labor strikes, equipment breakdowns, or accidents can shut down production overnight. Environmental regulations and fines can delay or derail projects. Juniors especially rely heavily on raising fresh capital, often diluting shareholders, and many are driven more by speculation than actual output. And importantly, all investments have opportunity costs associated with them—for most investors, more money can be made outside of gold mining than inside. Since investors can't invest in everything, they will naturally choose the most profitable opportunities, leaving capital-intensive miners at a disadvantage.

Looking at the supply side, the challenges are even more stark. In 2014, about one-third of the gold supply came from recycling. Today, annual mine output is about 3,400 tonnes (2024), but the total above-ground stock is roughly 210,000 tonnes. That means new supply only adds about 1.5% per year—slower than global GDP or population growth. Gold has an extremely high stock-to-flow ratio, which is why its monetary "inflation" is low and predictable, making it less dependent on new mine production than commodities like oil or copper, and more sensitive to shifts in monetary or investment demand. Almost all the gold ever mined still exists in vaults, jewelry, or reserves, so above-ground stock dwarfs annual mining.

But producing new gold is not easy. The average time from discovery to production is 10–20 years, and grades are getting lower, meaning more rock must be moved, driving costs up. No world-class discovery has been made in the last 30 years, and all the gold discovered in the last decade is less than half of what was found in a single year in 1990, when gold was under $400/oz. Between 2012 and 2020, the reserves held by major mining companies dropped by about 40%. Back in 1971, when gold was $35/oz, global mine production was about 1,500 tonnes. Fifty years later, despite the gold price rising roughly 6,000% (about 50-fold), mine output has only doubled to around 3,000 tonnesper year, averaging 1.5% growth per year—roughly in line with population growth. One could argue that new gold supply is effectively declining.

Company reports show the current situation: in 2023, Newmont sold 5.8 million ounces and reported 135.9 million ounces in reserves—a sharp jump from prior years, largely due to its acquisition of Newcrest. That equates to roughly 18–20 years of reserves at current production rates. Barrick mined 4.76 million ounces in 2023 and by 2024 reported 89 million ounces in reserves, suggesting about 15–20 years worth of reserves. Neither company is anywhere close to running out, but they also show little incentive to prove up significantly more reserves than they need to.

Longer-term, technologies may emerge to make lower-grade deposits economical or reduce toxic inputs like mercury and cyanide. Some even speculate about extracting gold from seawater or eventually mining metallic asteroids. But these methods are far in the future and extremely capital intensive. In the meantime, demand for gold and silver may rise with green energy and electronics, but efficiency gains and substitution limit long-term upside. For example, silver's share of solar panel costs is already down to 5–10%, and industry has cut silver use per watt by more than 60% since 2013. Copper, which is 95% as conductive as silver, is being pushed as a substitute.

In summary, mining is a notoriously difficult industry to invest in—marked by high infrastructure costs, questionable returns, depleting reserves, and leadership teams that are not always trustworthy. Capital intensive, huge pricing risk, inherently low growth, no moat, price takers, no value-adding, geopolitical risks, the supply is limited and comes in good/bad batches, cyclical no secular appreciation—whereas industries like insurance or beverages provide steady, reliable cash flows.

Will the first person to mine the astroid belt be the richest person in the galaxy?

The first person to mine the asteroid belt will probably die in the process because mining and space travel are both dangerous.

The money will be made not by the miners themselves, but by whoever develops the tools that the miners use. The owners of some of the mining companies will do well, but the companies that supply miners have traditionally made more money in the early stages.

…Depends on when we mine, but the first may involve people as well as robots.

If robots can do it on their own, then the robot and spacecraft manufacturers will make the most money.

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/visualizing-the-new-era-of-gold-mining/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-the-metals-we-mined-in-2021-visualized/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-the-metals-we-mined-in-2021-visualized/

Charted: The Value Gap Between the Gold Price and Gold Miners

Visualizing the Life Cycle of a Mineral Discovery - Visual Capitalist

Visualized: Major Copper Discoveries Since 1900

Junior gold miners in particular are like playing Russian roulette. The business is extremely capital intensive, often located in high-risk or high-labor-cost jurisdictions, and most of the world's easy, low-cost deposits have already been mined. Costs are relentlessly rising—labor is getting more expensive worldwide, mining expertise is scarce, and critical processing chemicals cost more each year. On top of that, junior management teams have a reputation for being no more trustworthy than used car salesmen or politicians, with a history of diluting shareholders or engaging in self-serving deals. Storage, transport, and sales logistics also add cost and complexity.

The economics quickly turn ugly if gold prices fall. For example, Harmony Gold (HMY) currently runs with a gross profit margin around 22%. If gold dropped by 40%, profitability would vanish. Mining stocks are capital-intensive, carry huge pricing risk, are inherently low growth, and offer no real moat—they are price takers selling an undifferentiated commodity. Supply is finite and comes in unpredictable, good-or-bad batches. The sector is cyclical, not secular, so it doesn't steadily appreciate over time. By contrast, investors who prioritize cash flow tend to prefer steady, reliable businesses like insurance or beverages.

On top of that, mining stocks carry company-specific risks: poor management, excessive debt, or legal liabilities. They are often more volatile than the price of gold itself, swinging with earnings reports and investor sentiment. Many operate in politically unstable regions, so risks of coups, nationalization, or sudden tax changes are ever-present. Operational problems like labor strikes, equipment breakdowns, or accidents can shut down production overnight. Environmental regulations and fines can delay or derail projects. Juniors especially rely heavily on raising fresh capital, often diluting shareholders, and many are driven more by speculation than actual output. And importantly, all investments have opportunity costs associated with them—for most investors, more money can be made outside of gold mining than inside. Since investors can't invest in everything, they will naturally choose the most profitable opportunities, leaving capital-intensive miners at a disadvantage.

Looking at the supply side, the challenges are even more stark. In 2014, about one-third of the gold supply came from recycling. Today, annual mine output is about 3,400 tonnes (2024), but the total above-ground stock is roughly 210,000 tonnes. That means new supply only adds about 1.5% per year—slower than global GDP or population growth. Gold has an extremely high stock-to-flow ratio, which is why its monetary "inflation" is low and predictable, making it less dependent on new mine production than commodities like oil or copper, and more sensitive to shifts in monetary or investment demand. Almost all the gold ever mined still exists in vaults, jewelry, or reserves, so above-ground stock dwarfs annual mining.

But producing new gold is not easy. The average time from discovery to production is 10–20 years, and grades are getting lower, meaning more rock must be moved, driving costs up. No world-class discovery has been made in the last 30 years, and all the gold discovered in the last decade is less than half of what was found in a single year in 1990, when gold was under $400/oz. Between 2012 and 2020, the reserves held by major mining companies dropped by about 40%. Back in 1971, when gold was $35/oz, global mine production was about 1,500 tonnes. Fifty years later, despite the gold price rising roughly 6,000% (about 50-fold), mine output has only doubled to around 3,000 tonnesper year, averaging 1.5% growth per year—roughly in line with population growth. One could argue that new gold supply is effectively declining.

Company reports show the current situation: in 2023, Newmont sold 5.8 million ounces and reported 135.9 million ounces in reserves—a sharp jump from prior years, largely due to its acquisition of Newcrest. That equates to roughly 18–20 years of reserves at current production rates. Barrick mined 4.76 million ounces in 2023 and by 2024 reported 89 million ounces in reserves, suggesting about 15–20 years worth of reserves. Neither company is anywhere close to running out, but they also show little incentive to prove up significantly more reserves than they need to.

Longer-term, technologies may emerge to make lower-grade deposits economical or reduce toxic inputs like mercury and cyanide. Some even speculate about extracting gold from seawater or eventually mining metallic asteroids. But these methods are far in the future and extremely capital intensive. In the meantime, demand for gold and silver may rise with green energy and electronics, but efficiency gains and substitution limit long-term upside. For example, silver's share of solar panel costs is already down to 5–10%, and industry has cut silver use per watt by more than 60% since 2013. Copper, which is 95% as conductive as silver, is being pushed as a substitute.

In summary, mining is a notoriously difficult industry to invest in—marked by high infrastructure costs, questionable returns, depleting reserves, and leadership teams that are not always trustworthy. Capital intensive, huge pricing risk, inherently low growth, no moat, price takers, no value-adding, geopolitical risks, the supply is limited and comes in good/bad batches, cyclical no secular appreciation—whereas industries like insurance or beverages provide steady, reliable cash flows.

Will the first person to mine the astroid belt be the richest person in the galaxy?

The first person to mine the asteroid belt will probably die in the process because mining and space travel are both dangerous.

The money will be made not by the miners themselves, but by whoever develops the tools that the miners use. The owners of some of the mining companies will do well, but the companies that supply miners have traditionally made more money in the early stages.

…Depends on when we mine, but the first may involve people as well as robots.

If robots can do it on their own, then the robot and spacecraft manufacturers will make the most money.

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/visualizing-the-new-era-of-gold-mining/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-the-metals-we-mined-in-2021-visualized/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-the-metals-we-mined-in-2021-visualized/

Charted: The Value Gap Between the Gold Price and Gold Miners

Visualizing the Life Cycle of a Mineral Discovery - Visual Capitalist

Visualized: Major Copper Discoveries Since 1900